|

WORLD WAR II COMBAT: THE TRIP OVER

Samuel Warren Cochran

Installed as a webpage on Shade Tree Physics on 05 Sep 2016.

Latest update 24 Oct 2016.

It was the middle of May in 1943. A year earlier I had earned my wings as a Staff Sergeant

Pilot at Ellington

Field, Texas; and from May 1942 until January 1943 I had flown student

bombardiers at Midland Airfield,

Texas. In December 1942, I was eager for combat, and my first opportunity to engage therein

was to be as a copilot on a B-26 Martin Marauder, reported to be the hottest airplane in the

Army Air Corps. Immediately, I volunteered for the position and, in January 1943, was assigned

to the 386th Bomb Group, 555th Bomb Squadron, at

MacDill Field, Florida.

Prior to departing Midland Air Field, I was promoted to Flight Officer.

While at Midland I had fallen in love with a lovely young lady named Polly Wingo. Everything

was bright and beautiful--in fact, very beautiful! I was in love--with Polly, with airplanes,

and with the sky, with flowers, and with music. "White Christmas" and "He Wears a Pair of

Silver Wings" were written in 1942."Comin' in on a Wing and a Prayer"-and "That Old Black Magic"

were written in 1943. I knew exactly what was going on, but I had to remind myself contstantly

that this was not a dream. I was farther away from home that I had ever been, thinking thoughts

that, to my mind, were reserved for the elite; doing things I had never even dreamed about; and

looking forward to a world that, up until this time, no one had ever experienced except a handful

of pilots who were members of the Royal Air Force (RAF).

I became the copilot on a near-ready combat crew: pilot, Lt. Robert L. Perkins;

bombardier-navigator, Lt. George Hazlett; radio man and gunner, T/Sgt. Alfred Lopez; engineer,

S/Sgt. Theodore Coyle; and tail gunner, T/Sgt. Leo "Red" Kirk. T/Sgt. Sampie T. Smith was our

crew chief. Before my first flight in the B-26, I purchased a pair of brown leather boots, the

type worn by all combat aircrewmen. We completed the remainder of our B-26 transition at MacDill

Field; then the 386th Bomb Group moved to

Lake Charles Air Field,

Louisiana, where we completed our training and became fully combat ready. We left our B-26s

at Lake Charles Air Field and departed for the European Theater of Operation (ETO) via a troop

train that carried us to Selfridge Field, Michigan.

Selfridge Field Michigan.

At Selfridge Field we picked up the airplane we would fly in

combat, a brand new B-26, model B. We spent several days checking our airplane, making sure it

was ready to fly us across the Atlantic. We swung the compass, checked and rechecked everything

every day, and gave special emphasis to the electrical, hydraulic, and fuel systems. We were

determined to learn the airplane--and we did. On May 18, 1943, convinced that our airplanes

were airworthy and capable of taking us across the Atlantic, to England, and into combat, the

386th Bomb Group started to depart Selfridge Field, Michigan. Our first leg took us to

Hunter Field, Georgia.

Hunter Field, Georgia. The

trip to Hunter Field was flown as briefed, and our crew arrived

on schedule. At Hunter we loaded extra airplane parts and supplies, weighed the airplane, computed

its center of gravity (CG), and refueled. We were issued Artic Kits. Prior to departing Hunter

Field, I was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the Army Air Corps.

Langley Field, Virginia. On May

26, 1943, we departed for Langley Field, Virginia, a refueling stop. The trip was flown as briefed.

Presque Isle, Maine.

From Langley Field our route carried us to Presque Isle, Maine, the last stop in the United States.

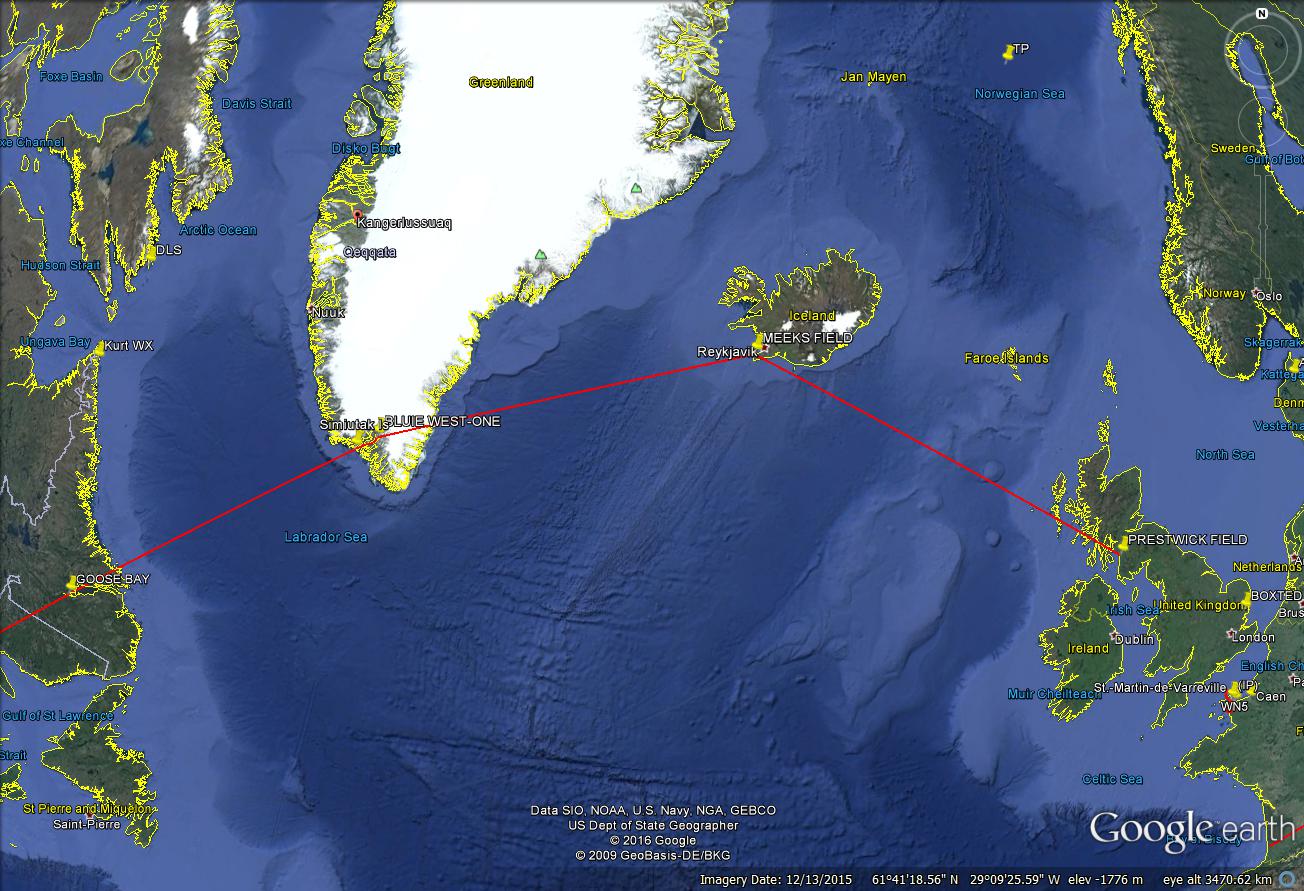

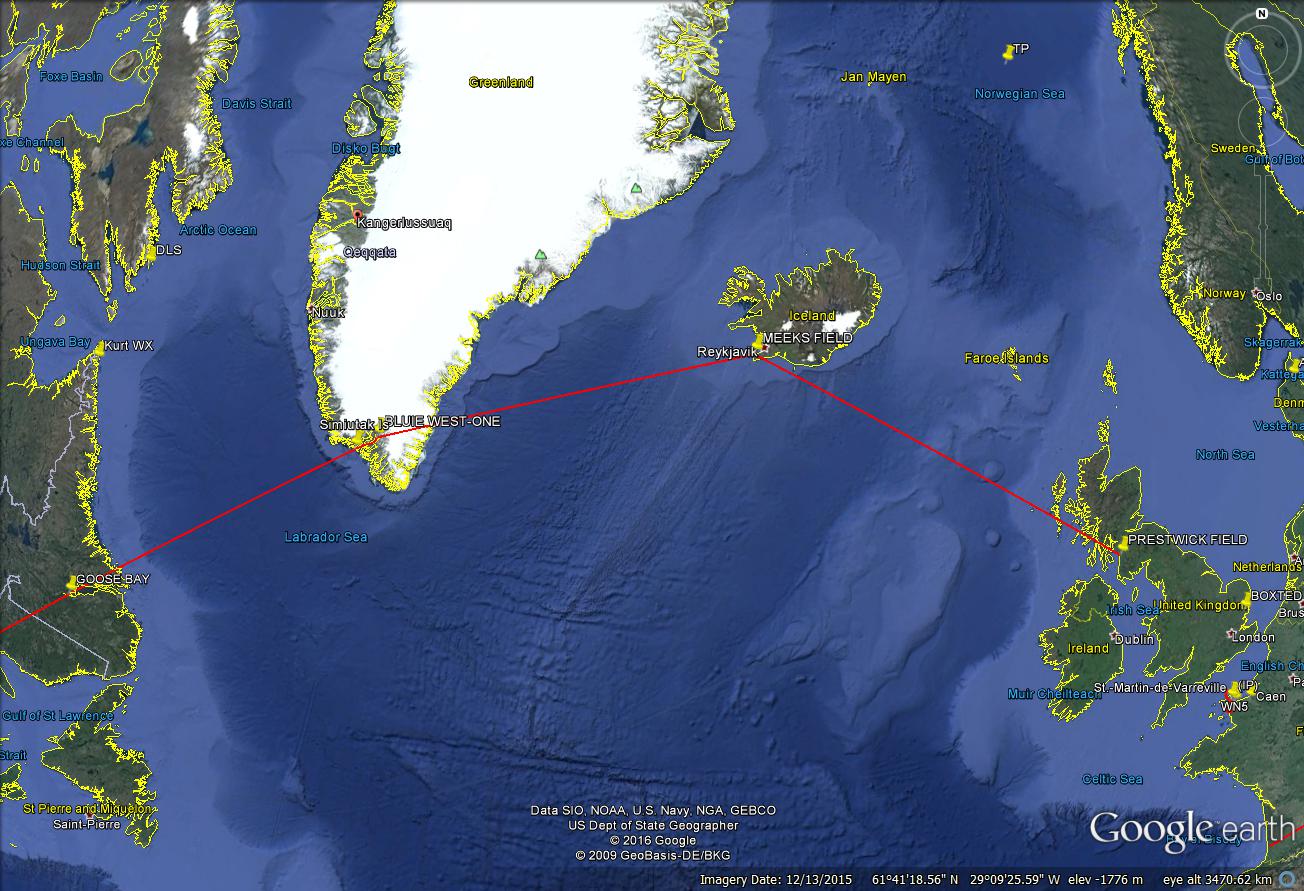

Here we received our briefing for the trip across the North Atlantic. On the last day of May in

1943, we departed Presque Isle enroute to Goose Bay, Labrador, a Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF)

Field. The flight to Goose Bay only took four hours, but it was a completely new experience. First,

this was the first time I had ever been outside the United States. Second, there were few

navigational check points, and the map showed little other than major landmasses and large bodies

of water such as the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Everything looked lonesome.

Goose Bay, Labrador. We arrived at

Goose Bay without incident, and landed between two

gigantic snowbanks, formed by snow that had been removed from the runway during the winter. Due to

the long hours of daylight at these northern latitudes, we refueled and proceeded to

Bluie West-One on the southwestern

coast of Greenland.

Trip Over, Page 2 of 3

Bluie West-One (BW-1), Greenland.

This was our first long flight over water, and about the only things we saw were icebergs. I was

thrilled--this was the first time I had ever seen the Atlantic Ocean or an iceberg. The ceiling

and visibility were unlimited (CAVU). I had never experienced clearer weather. We spotted the coast

of Greenland long before we thought we should and, for a few minutes, believed that we were

off-course. We re-plotted, believed our calculations, and stuck with our flight plan.

We had been briefed on the possibility of German U-Boats jamming our radio frequencies, but that

never happened. However, our route carried us near the Arctic Circle, where the magnetic compass

went wild; more often than not, the compass was in error more than 45 degrees. Because the magnetic

compass was useless, we depended on the directional gyro (DG), sun shots, and radio signals.

BW-1 was one of the most unique airfields in the world. It had a single runway of Pierced Steel

Planks (PSP). The runway was short for a B-26, less than 4,000 feet, and located about 50 miles up a

fiord at the base of a glacier. The personnel at Goose Bay briefed us on many of the characteristics

of BW-1, and we were shown photos of our destination. We calculated our "point of no return"--the

point where we did not have enough fuel to return to Goose Bay and must proceed to BW-1. This was

the first time that the point of no return was meaningful.

We learned firsthand that the coast of Greenland had dozens of fiords, and the trick was to

enter the correct one. In addition, we were warned that there were several "arms" of the correct

fiord; however, only one led to the runway. We had been shown the photo of a wrecked ship that

would help guide us to the correct arm, and we breathed a sigh of relief when we spotted the

shipwreck. We were flying up a canyon with a river at the bottom and expected to see the runway

around every bend. But no runway. . . no runway. . . then there it was! Wheels and flaps went

down; there was one more turn to the left, then a final turn to the right. We were almost there.

Overshooting meant crashing into the glacier at the far end of the runway, and undershooting meant

landing in near-freezing glacial water. We called all the shots right and completed the trip in

grand style.

Another dramatic moment came when we touched down on the PSP. There was no familiar screech of the

tires; rather, there was banging steel, pelting rocks, dissonant noises, and dust--all normal, we

learned later, for a PSP landing.

Even more dramatic events were yet to come. First, the food in the mess hall was the best I had ever

eaten. I had anticipated the food would reflect the Spartan environment of BW-1. Second, I could not

believe my ears--the radio in the mess hall was playing the same music we had enjoyed in the United

States. We were flabbergasted to learn that we were listening to a German radio station, and we had

difficulty containing our surprise when the announcer welcomed the 386th Bomb Group to Greenland. We

really perked up our ears when he welcomed each crew by name. This was our first encounter with the

enemy and a profound lesson in the need for security. The war in Europe was getting closer with each

revolution of the propeller.

Flying out of BW-1 was almost as interesting as getting in. All crews were briefed for the flight to

Iceland; then we waited for favorable surface winds and visibility. At BW-1 the only runway ran

uphill toward the glacier--airplanes always landed uphill and toward the glacier. Takeoff was in the

opposite direction, toward the water and downhill. The wait for takeoff was not long. We plotted our

route to fly over the icecap rather than around the southern tip of Greenland, which proved to be a

wonderful choice. The icecap was something to behold; how a person could get off the icecap was

beyond my imagination.

Meeks Field, Iceland.

Our flight to Iceland was pleasant, and we landed on schedule at Meeks Field in southwest Iceland.

During the flight, our magnetic compass did its usual erratic dance. This was an applicaton of what

we had learned in ground school--we were so near the North Pole that a magnetic compass was worthless.

I was viewing the world through different eyes, and I was beginning to understand some of the

navigational problems encountered by arctic explorers.

Trip Over, Page 3 of 3

In 1943, there were two main routes to Great Britain: the southern route through South America and

Africa and then up to England, or the northern route, which was the one we were taking. Each landing

field along the route could accommodate only so many airplanes at a time; and in Iceland, the northern

route became clogged, resulting in our staying there for nearly a week. Happy Day! This was my

introduction to a foreign country, a different language, and a different currency: the Icelandic

krona. The krona looked nothing like our greenback or silver--it was funny money. However, before

long I learned the US dollar-krona exchange rate, and the krona assumed a different value. I never

did ask if we were allowed to leave Meeks Field; but we could see a town a mile or so away, and

several of us walked over and purchased cookies with krona.

I did not see any trees in Iceland. Roads were made of lava rocks and fishbones. Puddles of water

along the road were as likely to be hot as cold. Amazing! Absolutely amazing! I fell in love with

Iceland, and my affection has continued until this day. I learned that Iceland continues to have

volcanic action, resulting in an abundance of hot water. In fact, natural hot water, as well as

cold, was piped into homes and buildings. Also, the southern coast of Iceland is located in the same

warm Gulf Stream that flows from our Gulf of Mexico. The southern seaports of Iceland remain open

practically year round, while the northern ports are closed much of the time. Swimming is a year-round

activity and one of the major sports in Iceland.

Save for vague and impersonal feelings, war was not in my value system, and I never had any specific

thoughts about combat. I had confidence in our B-26B, my skills, and the ability of each member of

our crew. Each rising of the sun brought an enchanting new day. I was beginning to understand the

feeling that Galileo, Newton, Columbus, Marco Polo, and Magellan must have had.

Eventually, the weather cleared; traffic on the northern route started to move. We were off to

Great Britain.

Prestwick Field, Scotland.

In our briefing, we learned that a stripped-down B-17 would meet us about 200 miles off the coast

of Scotland and lead us to Prestwick Field, our destination in Scotland. That seemed odd. We had

found Goose Bay, BW-1, and Meeks Field--so what was so special about finding our way to another

strange field?

We encountered our most severe weather between Iceland and Scotland but managed to fly through it,

located our mother B-17, and homed in on her radio beacon. After crossing the coast of Scotland, we

started our letdown and near Prestwick broke out of the clouds at about 1500 feet. The entire

landscape was covered with flowers of every color. The expanse of flowers was laced with scores

of meandering stone fences, creating the most majestic patchwork quilt in the entire universe.

As far as the eye could see everything was the same--beautiful, simply beautiful! For a moment,

locating the runway was not nearly so important as looking at the beauty of the countryside. Now

I understood why we needed an airplane to guide us. We landed at Prestwick Field on schedule.

Horrors!--I was in love again!--this time with Scotland! Over the next few weeks, I wondered about

my love for so many things and made a marvelous discovery: the more a person loves, the more

capable he is of loving.

Boxted Field, England. The next day

we reached our final destination: Boxted Field, England, northeast of London, near Colchester. We

flew our flight plan and arrived on schedule.

On May 18, 76 airplanes started their departure from Selfridge Field, Michigan, and all but three

were in place at Boxted Field, England, on June 16, 1943. Seven crewmen were lost in the movement.

The first thing I did at Boxted was to communicate with Polly.

Samuel Warren Cochran

5100 John Ryan Blvd. #635

San Antonio, TX 78243-3535

January 11, 1989

|

|