|

WORLD WAR II COMBAT: MISSIONS 1 THROUGH 72

Samuel Warren Cochran

Installed as a webpage on Shade Tree Physics on 11 Sep 2016.

Latest update 04 Jun 2018.

For about a year (June 16, 1943 to July 10, 1944), I was based in England and flew

aerial combat missions in B-26s over Europe. During this period, I flew 72

missions, an average of 6 missions a month, for a total of 204 combat hours. I don't

know why I stopped flying combat with my 72nd mission--but, yet I really do.

The B-26 has two engines, each of which produced 2,000 horsepower (HP); they burned

a high grade of aviation fuel, 100-130 octane. Its empty weight was 24,000 pounds;

and for that weight, the wingspan was short, 74 feet. The airplane appeared to be

made of a fuselage and two engines--but no wings. Depending on the company you were

in, the B-26 was referred to as a flying cigar, a bumblebee, or a flying prostitute

(no visible means of support). When the crews were in training, and for the first

couple of combat missions over Europe, it was referred to as the "widow maker." The

Martin Marauder cruised at 230 miles per hour, and its final approach speed was well

over 100 miles per hour, an unthinkable speed in the early 1940s. It had a service

ceiling of 21,500 feet, a combat radius of 575 miles, and normally carried 4,000

pounds of bombs. I joined the 386th Bomb Group as a co-pilot when the group was

almost ready for combat. Since our energy was devoted to the pursuit of the enemy,

there was scant time to upgrade co-pilots to pilots. Before joining the outfit, I

had accumulated considerable flying time, mostly in twin-engine airplanes (AT-9,

AT-11, B-18, and B34); and from the beginning, I fell in love with the B-26. Soon

after arriving in England, I checked out as pilot and flew some of my combat missions

as co-pilot, others as pilot. However, I never had my own airplane or crew.

Combat was brutally impersonal. We never touched bodies or saw blood; we never heard

tender voices or groans of agony; there was never a whiff of roses or the stench of

death--we simply destroyed targets. In the early days, one mission was about like

another. During briefing, our primary and secondary targets were announced, take-off

and rendezvous times established, initial point (IP) and bomb run pointed out,

bombload specified, and as much information as was known about enemy resistance--

flak and fighters--was given. We flew missions as briefed; the clock was king. We

started engines at precise times. We also took off, joined formation, rendezvoused

with fighter escort, arrived at the IP, made the bomb run, and released bombs on

schedule. Occasionally, we encountered enemy fighters, and most of the time we were

shot at by flak. Usually, some of the airplanes received battle damage; most returned

home, others did not. Except for our muted phrases, knowing glances, and an evening

meal that was more somber than usual, we never mourned our fallen comrades--there

were no memorial services; no flags were flown at half mast.

We started to fly combat in mid-summer, and now we were well into the fall--I had

completed nearly 20 missions. It was late in the day, and we were waiting near the

living quarters with our eyes glued on the east. We wanted to see who would be first

to spot the returning formation. "There they are!" We shouted. Six airplanes from our

squadron, the 555th, had gone on the mission--they were the high flight. We counted,

"one, two, three, four. Four airplanes!" "Only four!?" We could not believe our eyes.

We counted again and scanned the sky for stragglers. There were no stragglers, not

even one! We stood as still and as mute as stones--my mind was blank. After a bit, my

first thought was, "Shucks, more clothes to pack." As quick as a wink, I cast this

wretched thought from my mind, but as soon as I relaxed even a wee bit it popped

back in. Horrors! My personality became even more strange--try as I might, I could

not feel sorrow! There was only the cold impersonal thought that two of our airplanes

had not returned and that my routine was interrupted. Then I came to myself.

The same person was not living in my body that was there a few months ago. I had

become a barbarian and never knew I was changing! My new role as a savage was

comfortable--it helped me to be an efficient member of a crack combat crew and got

me through the days and nights. I was surviving; but whatever the price, I wanted to

be a human being again. "I don't know how to think like a human being," I mumbled,

"but I do know how to act like one--and will start this instant!" Immediately, I

returned to my quonset hut, tidied up my things, walked across the way and took a

shower, put on a Class A uniform, and went to the evening meal. From that day, I

kept my living area neat, always slept between clean sheets, and dressed each day

in Class A's for at least one hot meal. Wow--soon my mind followed my body! Gradually,

I became able to laugh and to cry again, to love and to hate, to feel happy or to

feel sad, and to be content or apprehensive. Hurrah, I was becoming more human by the

day! The danger of losing the human touch was my greatest fear in combat.

Missions 1-72, Page 2 of 5

At that time, we were members of the Eighth Air Force, and our assumption was that

our combat tour was 25 missions then home. Less than a month after this incident,

all B-26s were transferred to the Ninth Air Force, and we learned that there were

different rules for completing a combat tour. Some days we believed the tour was

35 combat missions; at other times, we thought it was 50--but we never knew for

sure. Now that I was back in charge of myself, I was determined not to let this

ambivalence get me down. I set my personal combat tour: 75 missions.

Imperceptibly, fall became winter, accompanied by relentless low clouds, poor

visiblity, and darkness. We believed that somewhere in this glob of oppressive

weather there must be cracks of clear weather that were large enough to allow

airplanes to take off and assemble in formation, see enough of the ground to navigate,

view the target long enough to aim and drop bombs, and then find our way back home

before dark. We were constantly on the lookout for these cracks. We did not use

radar--all of our flying, navigation, and bombing were done visually.

Attempting a landing was more delicate than taking off. Landing with a 500-foot

ceiling and a mile visibility was tricky. However, landing when the ceiling was 1000

feet and the visibility was a couple of miles was reasonable. Meteorological

instruments were not sensitive enough to predict such narrow margins--yet the

weather officer had to recommend to the commander whether or not the weather was

suitable to fly a mission. It was during these days that I started thinking about

probabilities. I wondered, "Could a weather officer make as many correct weather

decisions by shooting craps as he could when using his instruments?" I never answered

this question but, while pondering it, encountered thoughts that proved even more

interesting. When I observed that some of the weathermen were consistently better

forecasters than others, a new set of questions came to my mind, "Did some of the

meteorologists have better training than others? Were some just luckier with their

forecast? Did some of them have a feeling way down inside that more often than not

led them to a more accurate forecast?" I was surprised that this last question

entered my mind and was even more surprised that each time I cast it aside, the

question popped back in.

Everyone wanted to fly combat. Flight crews did everything possible to stay ready

for the next mission. It was common for ground-crew members to cross-train to become

gunners or toggleers (bombardiers). Flight surgeons, armorers, mechanics, and other

ground-support personnel forever were attempting to finagle a position on a crew and

fly a combat mission. They said that knowing what we went through helped them to

perform their jobs more effectively. But I knew better--combat had a pull!

It was as though a person were standing near a forest and heard contradictory voices.

One voice explained that the forest was dangerous and told him to go away. Cleverly,

the other voice never mentioned the characteristics of the forest; rather, it cast a

calm and mysterious aura and pulled him--gently, ever so gently--nearer and nearer

to the forest. This was a sinister game! The relentless voice, as soft as a puff of

cotton and as strong as a powerful magnet, enticed the person to enter the forest.

Combat was addictive!

The person learned that the forest was filled with hidden steel traps, cocked and

ready to snap. Horrors! Now the persuasive voice became a guide and confidant. The

voice spoke, "Come with me and I will show you the way out of this forest." "I can't

possibly make it past all those traps," the person protested. "But you can," the

voice replied, "You have been trained--you know how to detect steel traps, how to

maneuver, and where to step." The person argued back, "But, there is always the

unanticipated step that could prove fatal." "True," the voice agreed, "you may make

a misstep, but your chances of getting through are better than even." "They are!"

the person cried. "Yes. About 80% of traversing the forest depends on your skill,

and the remaining 20% on luck--you supply the skill, and I will supply the luck."

My favorie targets were marshalling (railroad) yards. Marshalling yards were easy

to find and, compared to bridges, were not difficult to tear up. Often, there was

something in the yard, perhaps a railroad locomotive with a boiler of steam or

boxcars containing explosives, that triggered secondary explosions--there was never

any doubt whether the bombs had found their mark. Fires that were set by the bombing

often sent billows of smoke thousands of feet into the sky. It was the Fourth of July

ten times over. However, most of the excitement of strikes was vicarious. Bombs hit

the ground slightly behind the

Missions 1-72, Page 3 of 5

airplane, blocking the view of the pilots. What was going on down below was described

to the pilots by the bombardier and gunners. Their description of events, coupled

with strike photos that we saw the next day, supplied vivid pictures for my mind.

There was another consideration. After the bombs were released we made haste to get

out of the hornet's next. Fighters were more reluctant to attack a formation than

stragglers, so the pilot had his hands full maintaining position in formation--the

safest spot in the sky.

My least favorite targets were coastal guns and shore defenses. Try as I might, I

can't think of one good thing to say about these targets! Well, maybe one thing,

these missions were shorter than inland targets. But this plus was outweighed by

the relentless flak and the massive concrete fortifications that housed guns and

shore defenses. Besides, our 2,000-pound bombs scarcely made a scratch when they

struck the bunkers--it was like attempting to demolish an anvil with toothpicks.

In the fall of 1944, strange objects started to pound Britain. They were flying

bombs. This was a new weapon

. . . we were baffled. The bomb had stubby wings and

was powered by an engine with a strange sound. The bomb flew about a thousand feet

above the ground and went so fast that airplanes and flak guns had difficulty

destroying it. We soon learned that as long as we could hear the whine of the

engine we were safe--the bomb had not reached its destination and continued to fly.

When the engine stopped, look out! A few seconds later, the bomb would hit the

ground and explode. We learned that the bombs originated from the Continent and

that, prior to launch, the Germans progammed a heading and supplied enough fuel

for the weapon to reach its intended destination. We called this the V-1 bomb.

No sooner had we learned to live with the V-1 than the Germans launched a more

lethal weapon. A powerful bomb would appear out of nowhere and explode without

warning. We learned that these bombs also came from the Continent and were

carried on a rocket shot high into the sky, then made a noiseless free fall to

their intended target in Britain. We called this the V-2 bomb.

Since it was nearly impossible to destroy these bombs in the air, a decision was

made by higher command to immobilize them before launch, and the B-26s were

selected for the task. We spent months bombing the launch sites of the flying

bombs. The code name for these missions was "noball." Bombing a noball was about

like eating unseasoned hominy grits--there was not much zip to it. Noball sites

were tucked away in wooded areas, and about as much as I could say about the

target was, "Today we bombed a set of coordinates near a certain bend in the

road." "Did you hit the noball?" the interrogating officer would ask in his

debriefing. "I don't know; I really don't know," I would mumble. "The gunners

told me they saw some dust when the bombs hit. Ask them, maybe they can give you

a better answer." But over the long haul, maybe we did destroy many of the

noballs, as the war wore on, V-1 and V-2 bombs appeared over Britain less often.

Did you know that the distance between the rails of a railroad track is less than

5 feet? When railroad trusses and arches are added to make a bridge, we are still

talking about a structure that is not very wide--maybe 30 or 40 feet. Now, imagine

a bridge for a highway. This is still a skinny piece of architecture--maybe a

couple of hundred feet wide. Visualize an airplane flying 2.5 miles above the

bridge at 230 miles per hour and attempting to hit a bridge with a bomb. Flying

parallel to the bridge a few feet off-course, to the right or left, meant that we

would return tomorrow. When we flew perpendicular to the bridge, our bombs were

likely to fall short or long--leaving the bridge untouched. Eventually, I learned

to like to bomb bridges--mostly for the challenge of it.

I had to change my mind about the proper technique to destroy an airfield with

bombs. My original idea was to bomb the airplanes while they were on the ground,

but I soon learned that they were seldom on the ground--they were up in the sky

with us. Then I said, "Aha, I have it. Let's destroy their runways!" However,

that also proved ineffective. The fighters could land in the grass as easily as

on a runway. Soon I realized my mind was caught in its own trap. "Why," I

recalled, "I had many hours of flying time before I ever landed on a runway."

We pulled ourselves out of this dilemma by bombing the fighters' fuel-storage

sites and maintenance areas. This was my introduction to the distinction

between strategic and tactical bombing. I enjoyed bombing airfields. "What was

it that fascinated me about destroying airfields?" I wondered. I ruled out

secondary explosions, as I never saw our bombs hit the ground. Airfields

provided a big target and, as often as not, had meager defenses--maybe that

was the key.

Missions 1-72, Page 4 of 5

Supply depots and fuel-storgage areas were more difficult to locate than were many

of the other targets, but I liked these missions.

I did not enjoy destroying defended villages. Now and then I became apprehensive and

would ask myself unanswerable questions: "Who are the enemy?" "Did all of the enemy

wear uniforms?" "Where are the battle lines?" I believed that somebody had a plan for

the war, and I wondered how far into the future the plan extended. "Did the plan

identify the structures that should be destroyed to enhance the current campaign and

identify the buildings that should be kept to ensure that civilization did not take

too many steps backward?"

Bombing troop concentrations gave me no pleasure.

We changed our combat strategy several times. In the beginning, we flew evasive

action "by the numbers." With the first encounter of flak, we turned a predetermined

number of degrees to the right or left, held our heading for a specified number of

seconds, then executed another turn to the right or left--all the time making our way

to the IP. Soon the Germans caught on and anticipated our maneuvers. Rather than

aiming directly at us, they aimed where they calculated we would be after

our turn. Wow, that was a shock! Not to be outdone, we devised countermeasures. In

areas where flak was expected, gunners threw flimsy strips of metal (chaff) from

airplanes--chaff looked like icicles for a Christmas tree. Each tiny piece of chaff

became a target on the enemy's radar, effectively hiding our formation of bombers.

We flew in comparative safety--for a while. Then came the barrages! Flak gunners

anticipated our course to the target and, at a point where they believed we must fly,

kept the sky saturated with flak. The first time I saw a flak barrage, my thought

was, "My, what an ingenious idea!" My second thought was "What a waste of ammunition."

Then I saw it clear as day: I was an actor in a microcosm. This is what war really

is--technicians implementing a strategy that wastes resources. Almost immediately, I

returned to reality. Up ahead we could see the sky black with flak. The Germans had

guessed right! It would only be a matter of minutes before we would be in the middle

of their barrage. I did sneak in another thought before we got there: I wondered what

were the probabilities that we would make it through. Then I remembered mathematical

probabilities did not apply here--luck was on my side.

I never treated flak casually. On a 10-point scale of threat, it rated an 8; fighters

came in about 3, and mechanical problems with our airplanes rated a scant 1. In

addition to the smoke, noise, and destruction created by flak, it had a putrid odor.

Was it sour, or rancid, or did it smell sweet? I never knew. Flak fumes seemed to

stick to me--they penetrated my clothes, my hair, and my body; it took vigorous

washing to remove the odor. After a mission and debriefing, my first stop was the

shower.

During my 72 missions, our crew never aborted an airplane and no one was hurt--the

enemy never drew one drop of blood. We had many close calls; and when I first started

to fly combat I found myself exclaiming, "But what if . . . !" "Look at that hole--

if my head had been up just two inches, the bullet would have gone right through my

skull!" A gunner would report, "Number five airplane just fell out of formation, and

his number two engine is smoking like crazy." I would ponder the thought, "If we had

been a few more feet to the right that would have been us." Then I remembered Uncle

Frank's admonition: "Warren, if frogs had wings, they would not bump their behinds so

much." My mother prettied it up a little when she insisted: "Son, if wishes were

horses, all beggars would ride." The facts were: My head had not been up two inches,

and our airplane had not been a few feet to the right.

My belief was that since the beginning, war has changed little. War always has been

characterized by danger, waste, confusion, and grief. I have no idea how many flak

holes our airplane received. I had little interest in such things and never kept

count; my interest was in keeping my skills sharp and destroying targets. Come to

think of it, I do recall that at least one time we returned from a mission on a

single engine. Also, on one occasion, perhaps others, we could not lower all of our

landing gears and had to crash-land. However, none of our crash landings were

unanticipated or uncontrolled.

Missions 1-72, Page 5 of 5

Conversation when on a mission was to the point. We conducted routine internal

commands, reports, and procedures--ready the guns, fighters at nine o'clock low, that

flak is tracking us, open bomb-bay doors, bombs away--by using the radio within our

airplane (intercom). We also used the intercom to keep ourselves informed of the

condition of other airplanes in the formation. Messages were acknowledged by, "Roger."

The pilot, co-pilot, bombardier, and top gunner could see each other fairly well, and

we kept in touch with body language. A slight nod of the head meant, "Man, look at

that flak barrage up ahead!" Pointing to the sky meant, "Keep your eyes on those

contrails--could be ME-109s are out today!" A slight wave of the hand accompanied by

a friendly face meant, "Look at that sunrise! Have you ever seen anything so beautiful?"

Hand signals or facial expressions revealed bombing accuracy. We could communicate

with other airplanes in the formation by radio, but most of the time there was little

need to do so.

One of my minds kept reminding me that on this mission or the next, I may be shot down,

injured, or killed. But I never paid much attention to this mind--it had little influence

on my behavior. Early on, I learned a couple of valuable lessons: Making a

bomb run into the sun was futile, and making a second pass at a target was insane. I

suppose flying combat missions frightened me. During a mission, my mouth would get so

dry that I had difficulty talking. No matter what the temperature, I did a lot of

sweating; and at the conclusion of a mission, my legs and knees shook.

On Monday, July 10, 1944, there was nothing unusual about my 72nd mission. However, at

the conclusion of the mission, I heard a voice down inside of me say, "Sam, you have had

enough; it is time to stop."

"No, no," I protested. "Last fall I set my goal for 75 missions, and I have only three to

go. The enemy is wearing down--missions are becoming easier."

"Sam, you were the one who set the goal for your combat tour; you can be the one who

changes it," the voice argued. "Your skill is still there, but your luck is not. It takes

both skill and luck to survive--it's time for you to stop."

I said, "O.K." But, I can't believe I said O.K.! A year earlier, I would not have heard the

voice, much less followed its suggeston.

After debriefing and a shower, I went directly to the orderly room and saw the executive

officer, Capt. Herbert Lowe.

"Hi, Herb, I'm about ready to go home."

"Fine, Sam. I was wondering when you would drop by. I will start immediately processing your

paperwork. You will be on your way home in a few days." He continued, "What are your plans

after you return to the States?"

"I don't know for sure, Herb. I love to fly, but I need more education. My long-range plans

are a little vague."

"Do you have any immediate plans, Sam?"

"Yes, Herb, I do," I said with a smile. "The first thing that I am going to do when I get

back to the States is ask Polly Wingo to marry me!"

San Antonio, Texas 78245-3535

April 17, 1989

Postscript

The following information is copied from:

http://www.b26.com/guestbook/2003.htm

Date:12/21/2003

Time:12:52 PM

Comments: I looking for the names of the crew of a 555bs, 386th BG Marauder shot down

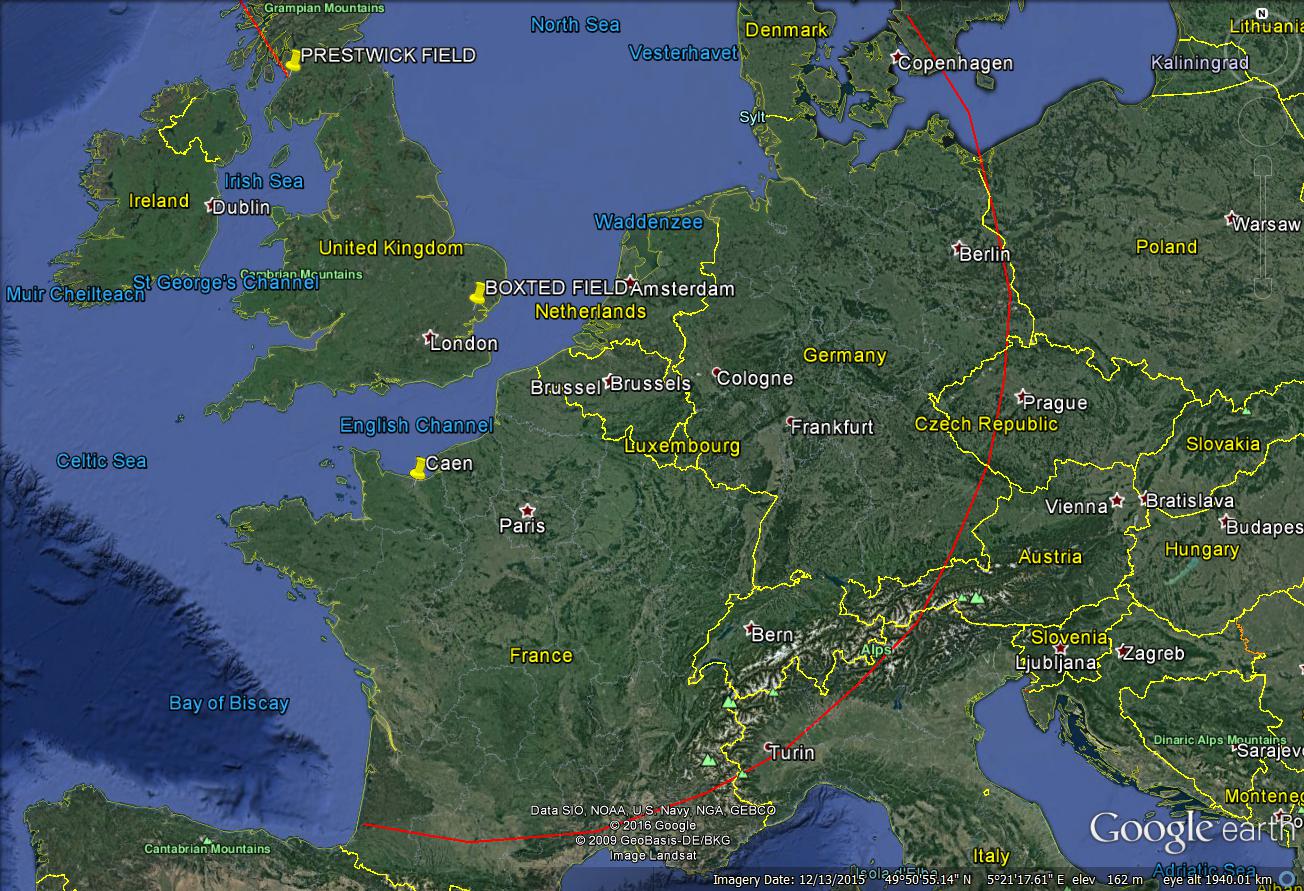

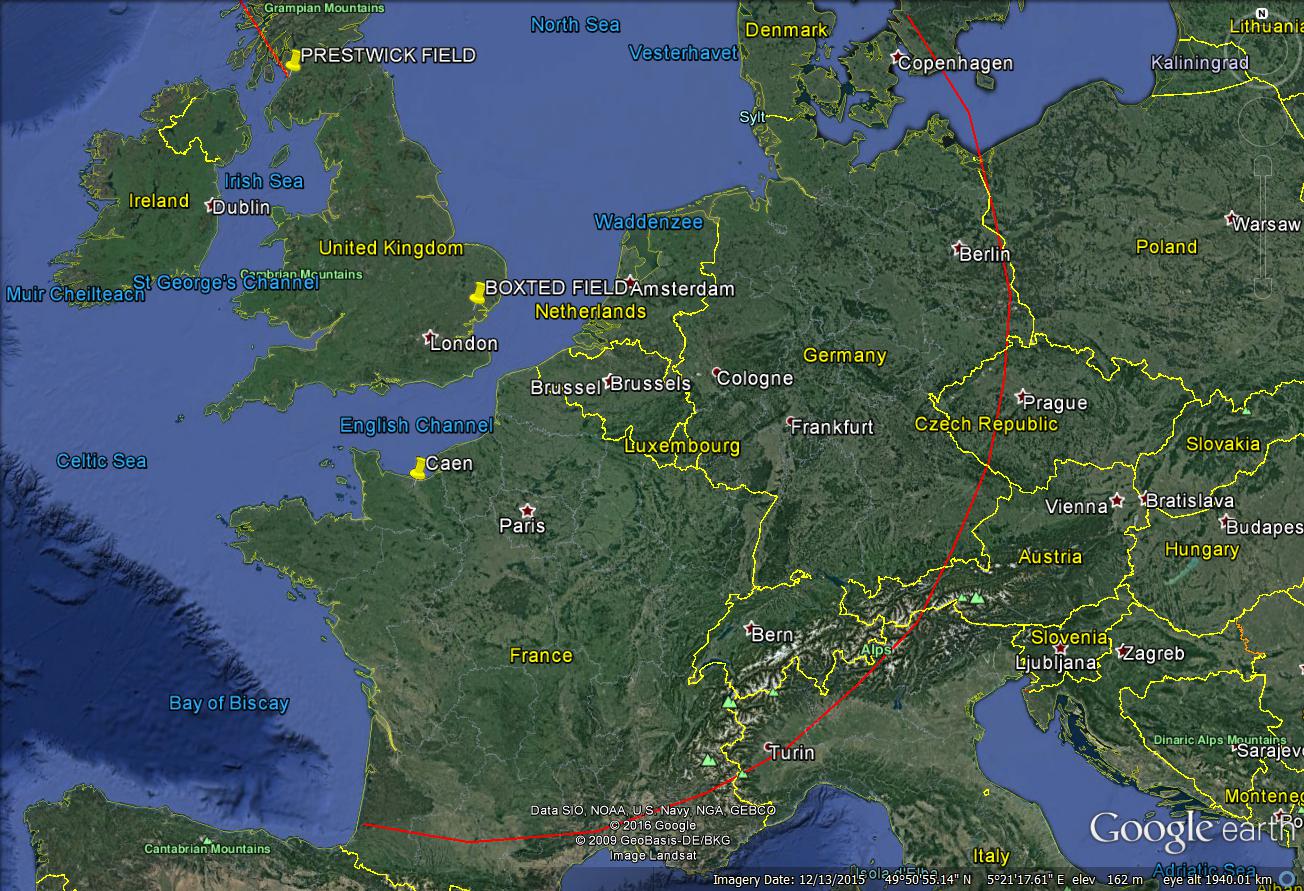

on the 18/6/44 over Caen. The only survivors were Bob Perkins and Sam Cochran both 555BS.

Who were the other members of the crew who were KIA? Pete Oliver, B26 fan.

Capt. Perkins, Lt. Cochran crew.

Email: BombGp: 386th Squadron: 555th Comments:

Hello Pete:

The Perkins crew was shot down on July 18, 1944. It was the 69th mission for Captain

Robert Perkins. His co-pilot was Lt. Samuel Cochran, on this particular mission Cochran

was flying in the left seat. Perkins was serving as co-pilot. It was Group mission

number 232. The target was in the Caen, France area. "MISS X" was the name of their

plane, tail number 296324. The crew listing: Capt. Perkins pilot, Lt. Cochran co-pilot.

T/Sgt. Adolpho Lopez radioman, S/Sgt. Leo Kirk tail gunner,

S/Sgt.Ted Coyle engineer,

and S/Sgt. Edward Murray bombardier. All of the enlisted men were killed when their

plane exploded in the air. If you would care to learn more about the 386th B.G.

operations check out my web page listed below. At present there are 86 stories and 79

bomber formation diagrams, plus 10 pages of photos.

Tallyho!

Chester P. Klier--Historian, 386th Bomb Group Group

Samuel Warren Cochran, Lt. Col USAF Ret, PhD, age 81, passed away on June 5, 2003.

See his

Obituary, courtesy of Porter Loring Mortuaries, San Antonio Texas.

The Obituary Page includes a copy of a San Antonio Express and News article

with details of his capture and survival after his crew's plane had been brought down.

|

|