|

WORLD WAR II COMBAT: D-DAY

Samuel Warren Cochran

Installed as a webpage on Shade Tree Physics on 11 Sep 2016.

Latest update 07 Oct 2016.

After the defeat of Rommel in North Africa and the Allies' invasion of italy,

it was generally believed that the invasion of the European Continent from

the north--through Holland or France--was only a matter of time. However, we

never talked much about it.

In the spring of 1944, a pattern to our nearly year-long bombing raids was starting

to emerge. Whether striking targets in Belgium, France, or the Netherlands, we

placed as much emphasis on making sure that we did not damage certain bridges, roads,

railroads, or terminals as ensuring that other targets were rendered useless. "Aha,"

I reasoned, "General Eisenhower and his staff are developing invasion plans." I did

not know how the 386th Bomb Group was going to fit in but was confident that we were

included. By now, the possibility of an invasion was becoming more real, and we

enjoyed speculating about the exact time and place.

Based on our bombing missions, I reasoned that the Allied Forces would invade the

Continent on the west coast of France, somewhere between Calais and Le Havre. By the

latter part of May, we believed that the invasion was imminent; and on one or two

occasions, our bomb group was placed on alert. Leaves were cancelleed--hush, hush

was everywhere--and we thought the next briefing would announce the invasion. But it

never did.

Late in the afternoon on June 5, we heard that white and black zebra stripes, about

18 inches wide, had been painted on both wings of our airplanes, around the

fuselage and on the tail. Wow, this was it! No one was allowed to leave the base,

and we did not talk among ourselves--everything was conspicuously tranquil. We all

knew what was about to happen, but we attempted to behave otherwise. Before dark,

the crews scheduled for the next mission were posted and our crew's name was on the

list. I was pleased.

About 2 on a 10-point scale, I knew this was going to be an historic mission; but

about 8 on the scale, I was more concerned with the technical part of getting the

mission completed successfully. By this time, I had flown more than 60 combat

missions and, reduced to its simplest terms, was determined to treat this as just

another mission.

At 2:00 a.m. on Tuesday, June 6, 1944, we assembled in the briefing room--it was

raining. The operations officer called the roll--everyone was present. Col. Joe W.

Kelly started the briefing with the statement, "Gentlemen, this is it!" I was

determined to keep calm--and did--but I must tell you that a cold shiver ran up

and down my spine. Colonel Kelly told us that earlier in the night 20,000 allied

paratroopers had been dropped on the Continent near the French coast. And at this

moment, heavy bombers were enroute to destroy targets in the invasion area. Except

for the crisp voice of our commander, all was quiet in the briefing room; for the

first time, I was aware of the drone of airplane engines overhead. I blocked out

everything else and continued to listen carefully to the engines overhead. My

mind was wanting me to conclude one thing, and my senses were telling me something

else. I overruled my mind and went with my senses: These airplanes were flying

more southerly than southeast! "Headed south!" I muttered, "Why, they must be

bound for Normandy!" Had I missed my guess about the location of the invasion--or

was this only a diversion?

I allowed my mind to return to the briefing; and in an instant, I knew I had not

missed anything--Colonel Kelly was letting each word soak in. We learned that the

"white and black D-Day zebra stripes" that had been painted on our bombers were

for identification. Every Allied aircraft wore them. Invasion personnel knew that

all airplanes without zebra stripes were enemies and should be destroyed on the

spot. "Betrayed!" was my first thought. "My intensive training in aircraft

identification had been telescoped into a five-second one-liner!"

Soon, I learned that I had missed my guess about the location of the invasion--it

was to be in the Normandy area. I hoped that the German HIgh Command also had been

fooled. We continued to learn about the grand scheme of the invasion: countries

that would participate (Britain, Canada, and U.S. Forces) number of personnel

involved, number of airplanes, and number of ships and boats. I was listening

to every word but was unable to comprehend the magnitude of the operation. Above

the sound of rain on the roof, I heard the constant roar of flying airplanes. We

had not completed our invasion briefing and already thousands of soldiers and

airmen were active. Where did we fit in?

D-Day, Page 2 of 2

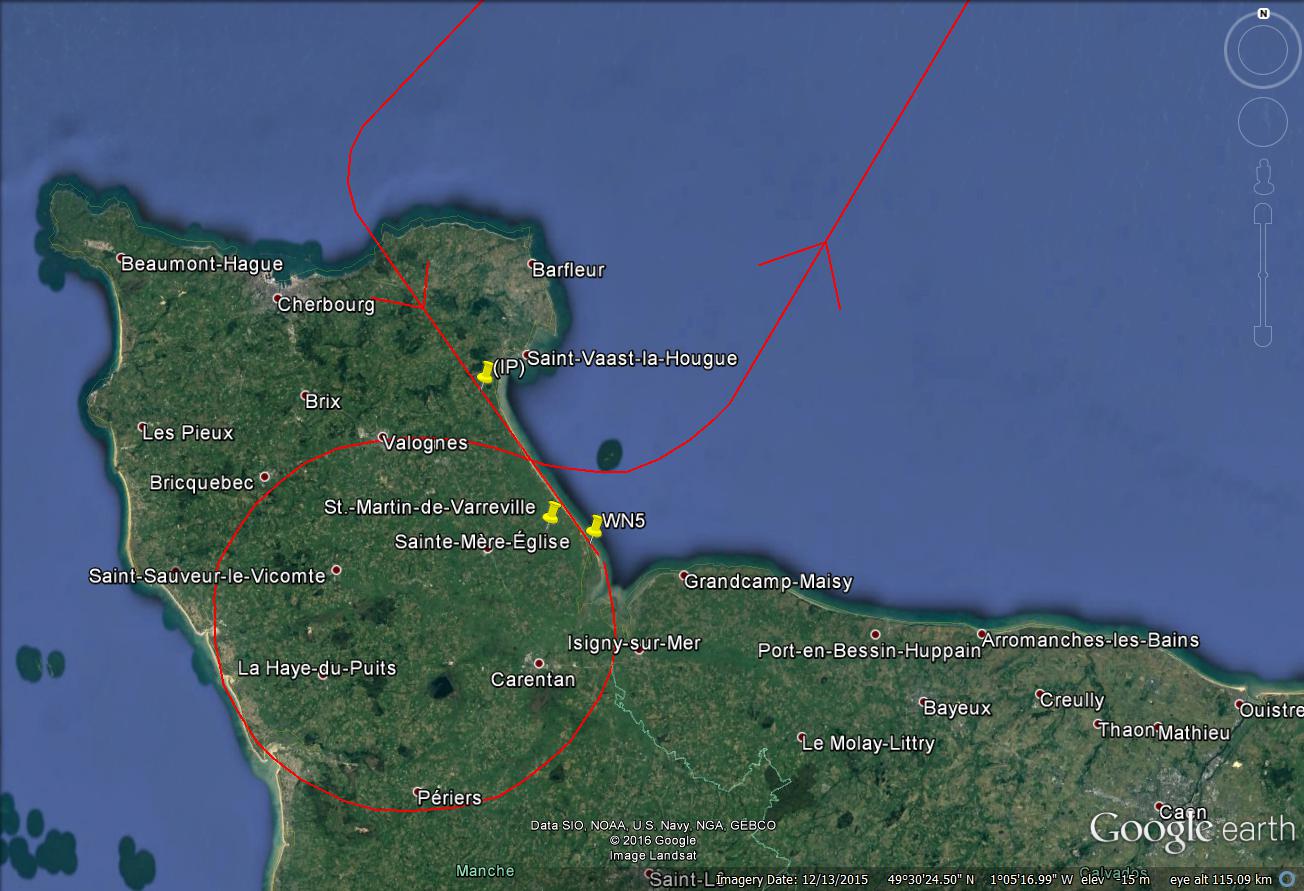

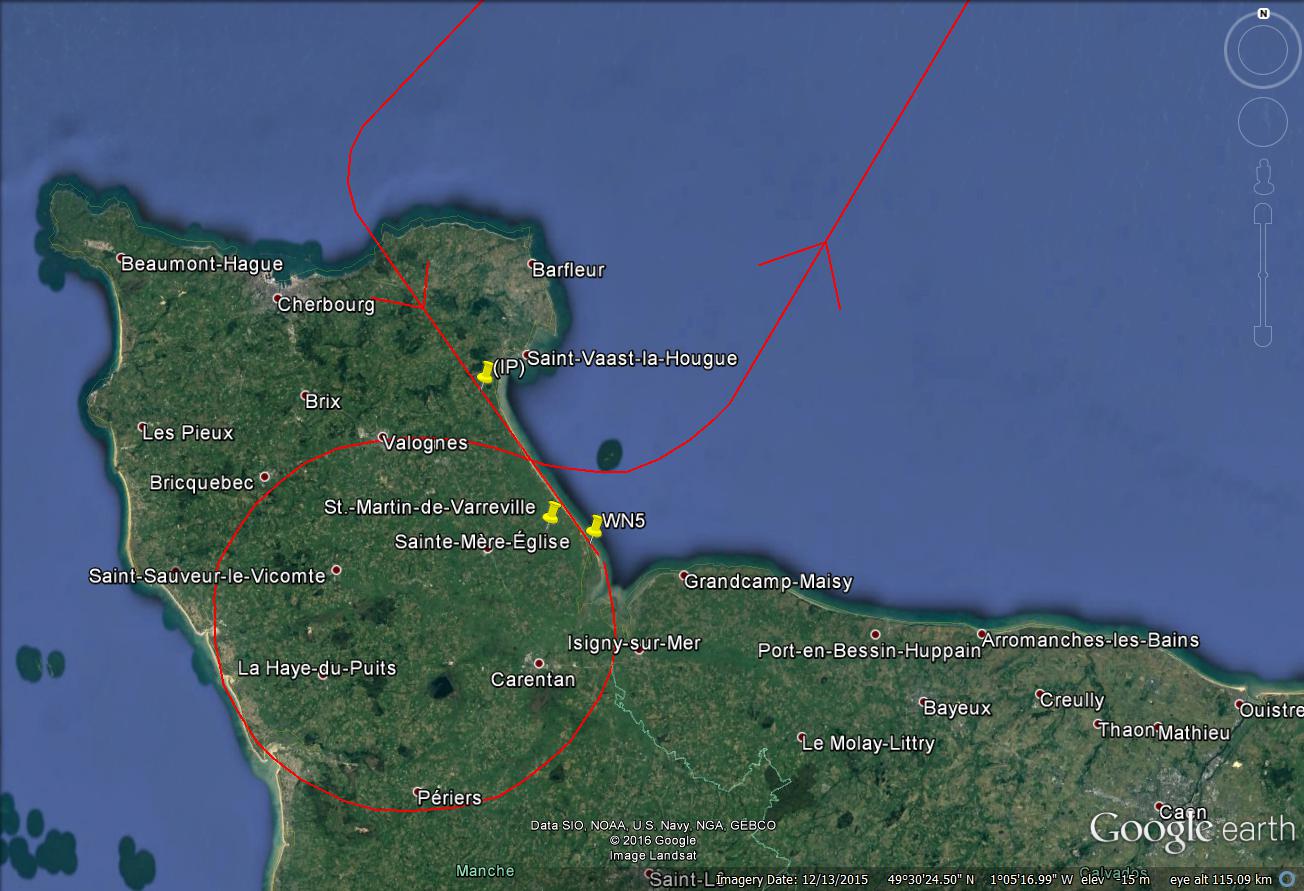

The intelligence officer identified our target. We were to drop our bombs on Utah

Beach, in the St. Martin de Varenville* area. But, what about timing? Then I heard

that the 386th Bomb Group had been awarded the place of honor in the invasion--we

would be the last to bomb before the ground troops stormed the beaches; however,

my mind could not believe what my ears were hearing. My mind and my senses engaged

in a tenacous battle. Then I started to reflect. *[St. Martin de Varreville.]

We all knew the 386th Bomb Group had the best bombing record of all Medium

Bombardment Groups in the European Theatre of Operations (ETO); however, we never

gave it much thought. We expected this of ourselves. Since our first mission,

we often had been assigned the more difficult targets and ocasionally had been

called upon to destroy a bridge or road after others had failed. Our bombing

accuracy was a function of self-preservation--not a desire for glory. In our

fondest dream, we had never sought this prestigious position in the D-Day armada.

Early on, we learned that when we did not hit the target the first time, we would

return the second time, or third. When a target was destroyed on the first attempt,

the defenses usually were lighter than on a later attempt. Since the Germans were

not capable of defending every target, they probably relied on our activity as a

measure of importance. Our aim was to do it right the first time. But we did have

a reputation, and it followed us. Things were beginning to make sense--but I paid

a price. I started to shiver, but I never knew whether I was shivering because my

clothes were damp, or because of our role in the invasion, or because my mind was

active, making sense out of mysteries. Now I was beginning to understand why

General Eisenhower had visited our bomb group a few months earlier.

Each B-26 carried 250-pound bombs. This size bomb would detonate land mines, knock

out fortifications, and make craters to serve as foxholes. It was still dark and

raining hard when we made our way to the airplanes; start-engine-time was 4:25. The

weather was forecast to improve as we reached the invasion area--but that was

trivial. No one ordered us to do so, but each aircrew member knew the mission would be

flown as briefed--against all odds. The concept of dedication was viewed through

different eyes.

We took off without incident, assembled our formation under the clouds, and headed

south for Normandy. After departing the English coast, our weather started to clear;

and when I was able to see the water, I could not believe my eyes: boats and ships

covered the English Channel! My first thought was, "Why, there is no place to ditch

an airplane!"

Timing was critical--to drop our bombs too early or too late would mean disaster.

Then I came to myself. Timing, when bombing, was always critical. I remembered: I

had resolved to fly this mission, using the same techniques as previous missions.

We arrived at our initial point (IP) as briefed, made our bomb run in a easterly

direction, flew below the clouds at 3,000 feet--the lowest altitude a bomb run

had been made by a B-26 Marauder in more than a year--and dropped bombs as briefed,

H-Hour minus 5 minutes. After we closed our bomb-bay doors, I looked to the left,

and a couple of hundred yards away there they were: countless landing barges filled

with soldiers poised to hit the beaches. It made no difference to me whether

American, British, or Canadian soldiers were in the barges--all were my allies. I

knew the enemy was to my right, but I never saw him. We were flying the cutting

edge. For a moment I allowed my mind to wander: it dawned on me--I had no

philosophical or theoretical basis to identify some of the strangers as friends and

others as enemies. But I pulled my mind back and got busy with the task at hand--we

had a mission to complete!

We encountered some flak and small-arms fire over enemy territory, but both were

light; all the airplanes that we saw had zebra stripes. After dropping our bombs,

we made a huge right turn, crossed the the Cherebourg Peninsula, and headed north

for England. On the leg home, we flew near the beaches where we had bombed a few

minutes earler; when I looked to my right, I saw hordes of soldiers coming

ashore--I had a ringside seat for the invasion.

San Antonio, Texas 78245-3535

February 16, 1989

|

|